Norman Hallendy was bestowed with the name Apirsuqti (“the inquisitive one”) by the Inuit elders of Cape Dorset, Nunavut, for his insatiable curiosity to learn from them and document their stories, experiences and insights in a vanishing world as it transitioned from a life on the land to one in settled communities. After Hallendy’s first encounter with the stone structures called inuksuit in 1958, he began travelling throughout the Arctic to learn as much as he could about the mysteries of inuksuit and the sacred sites of the Inuit. Hallendy earned the trust of the local inhabitants, who allowed him to observe their culture firsthand speak with them about subjects usually forbidden to outsiders (such as old beliefs and shamanic ways), and to formally document the people, their lives and environment in words and images. For Hallendy, it became both a determined scholarly undertaking and a lifelong labour of love.

Inuksuk Upigijaugialik is an inuksuk that is admired and respected by the Inuit for its age and size, and the belief that it was built by their ancestors, the Tunniit. Some inuksuit were believed to have spiritual qualities. They were venerated because of their connection to places of earthly and spiritual power. They may have signified places where spirits resided, shamans were initiated, traditions were observed, or judgments made. Or, they marked places for celebrations and festivals, or warned of dangers such as treacherous water, dangerous ice, and falling rocks.

On another path, Hallendy’s long relationship with the McMichael Canadian Art Collection began in 1980 when he donated a sculpture by Inuit artist, John Tiktak, which was followed by another art donation nine years later. Along with the 1989 gift of Inuit prints, drawings and sculpture, the donor began an even more important tradition. Over the next 25 years, Hallendy gradually entrusted his life’s work on the Arctic to the gallery, until eventually in 2015, The Norman E. Hallendy Archives was complete. His documentary photograph collections and his ethnographic research on Inuit culture will provide the context for the Inuit art in the McMichael’s holdings, and more broadly, help to preserve a cultural heritage.

The Hallendy Archives consists of more than 12,000 still images including Kodachrome slides, photographs (black and white, and colour) and negatives which Hallendy captured with 35mm cameras. The image collections reveal details of traditional life and communities, and the environment of southwest Baffin Island, Nunavut. The photographs of people provide an invaluable primary source of information, especially about artists and their artistic processes (printmaking, engraving, carving, textile printing and sewing).

The second and more unique component of The Hallendy Archives is the ethnographic research collection, which was donated in 2015. The collection of primary and secondary ethnographic research material documenting the intellectual and material culture of the Inuit of the southwest Baffin area, consists of more than 46 hours of original video archives, an unprecedented semantic field database, art, maps, a book collection, and other important primary and secondary research materials.

Pudlo Pudlat, 1968, Photograph by Norman Hallendy, Inuit Artists of Cape Dorset Collection, Gift of Norman E. Hallendy, 1991. McMichael Canadian Art Collection Archives. ARC-NH1991.89.17A-19A

Beginning in the late 1950s, Hallendy nurtured a close relationship with the people, which enabled him to document an extensive body of traditional knowledge. In keeping with contemporary ethnographic practice, he lived among the people, participated in their everyday life, learned their language, and experienced their physical environment. As a result, he was accepted and trusted by the community which gave him invaluable opportunities to observe the culture directly and interview the people openly. Today, he is recognized for his accomplishments as one of the world’s foremost Arctic ethnographers, and an expert on inuksuit and Inuit sacred sites.

Hallendy studied the Inuit culture, recognizing the importance of preserving those aspects of an indigenous culture which UNESCO terms as “intangible cultural heritage.” It is widely accepted that a society’s “intangible cultural artifacts” are as significant as tangible material objects in defining a cultural identity. The intangible assets are the wealth of traditional knowledge, such as language, legends and stories, feasts and celebrations, songs and music, knowledge of natural spaces, healing traditions, beliefs and cultural practices, as well as skills and customs required for survival. These are passed from one generation to the next, through example, oral tradition and experience. In societies of this type that do not depend on the written word for communication, the elders of a community become the social archive and keeper of the information until it is passed on. Hallendy had the foresight to take a proactive role in preserving their traditional knowledge. He recognized that the elders had insights that could potentially be lost to future generations if not formally preserved. In turn, the elders saw the value in what Hallendy was doing, and wanted to share with him the experiences and stories that defined their way of life.

The shaman’s initiation site was a place of power, to be treated with the greatest respect. Naturally occurring, distinctively shaped stones would mark the pathway to an initiation site. “At some religious sites, only by leaving your footsteps on a particular path called the apautaujaq could you hope to evoke the spiritual powers latent in such places….Places of power and objects of veneration have a path, an arquti, leading to and away from them. There are invisible pathways not only to places of power but within places of power; their locations were rarely revealed.” (Norman Hallendy, Inuksuit: Silent Messengers of the Arctic (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2000, p.96).

Upon his first exposure to the Arctic, Hallendy felt a spiritual connection to the land. The special kinship with its people soon followed. It must have been destiny that brought Hallendy to Cape Dorset in 1958, placing him in the perfect position to observe, document and ultimately serve as the conduit for a culture in transition. With the elders of the community supporting his efforts, it became his calling to preserve the traditional knowledge for the next generation. He combined systematic field work with insightful observations gleaned from engaging with people, especially while being “out on the land.” Hallendy was successful in this because he was respectful of his subjects. The elders trusted him to record what he was told, without interpreting, judging or altering. Hallendy instinctively knew what kinds of questions to ask, and how to ask in a way that encouraged the elders to share. His research gathered practical traditional wisdom, but also insights into their thoughts, feelings and views of the world – the latter of which would be lost forever with their passing.

For almost 50 years, Hallendy embraced a methodical approach to his research. He took detailed field notes when collecting stories and other accounts; recorded and examined places, objects, environments, conditions and language; and documented people and places in photographs. While Hallendy had become fluent in Inuktitut, he also used local translators when interviewing the elders to ensure that he was recording their accounts exactly as he was told. Between 1990-2001, through 23 hours of videotaped “conversations, he recorded people as they talked about everything to do with life, from the pragmatic knowledge integral to their existence to the related personal and spiritual aspects of their lives. It was by choice of the individual elders to speak about surviving on the land, preparing skins, their language, their ancestors and building inuksuit – or to delve deeper into shamans, spirits, life values and places of power. Additional video footage depicts community life and the Arctic landscape. In addition to his published books and the lectures he delivers worldwide, Hallendy creatively took his primary research and produced original maps of Southwest Baffin Island which chart locations of key sites (such as inuksuit, traditional camps, hunting grounds, archaeological sites) that he learned about from the elders and others.

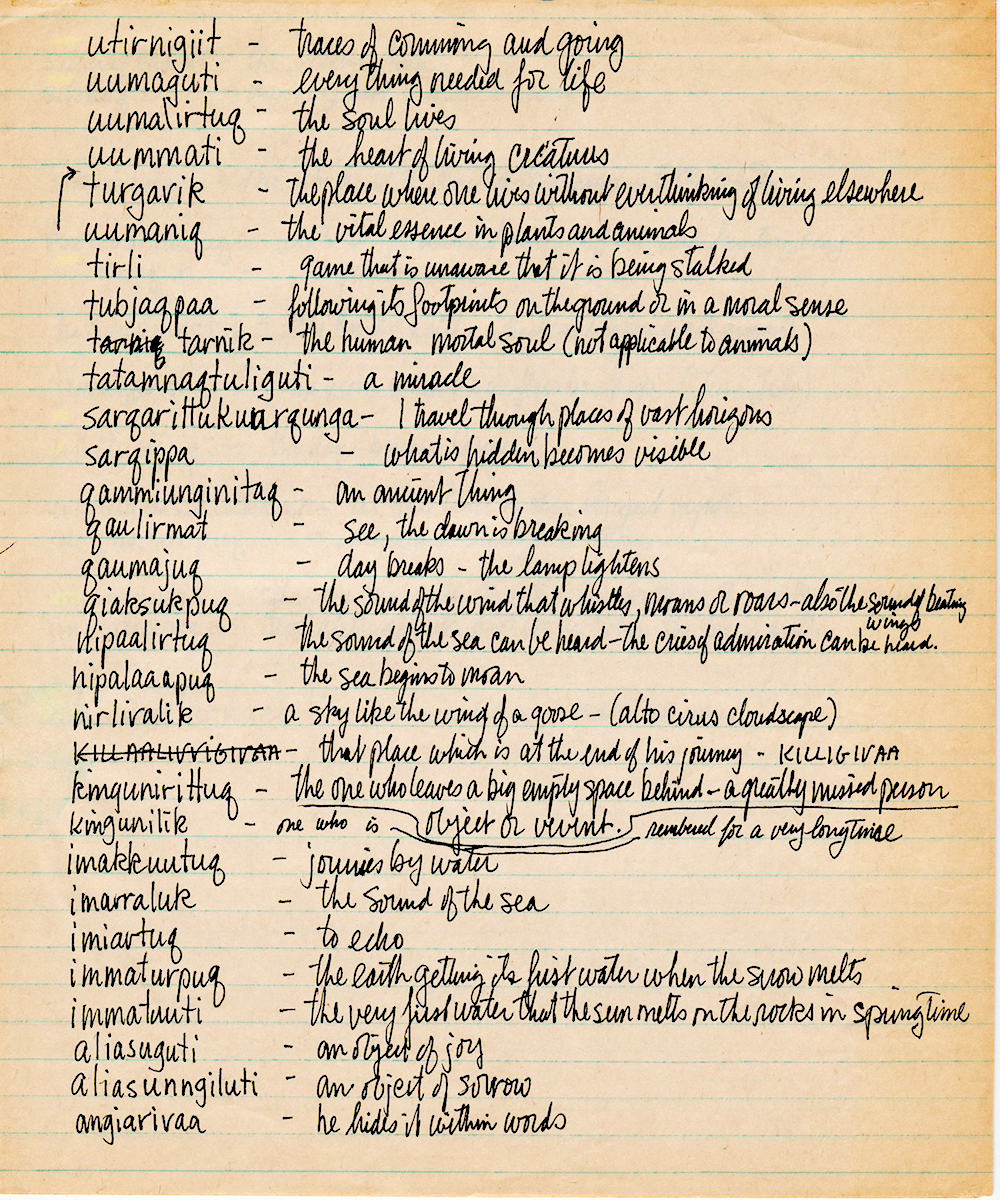

Another compelling component of the Hallendy Archives is the semantic field database, which is more than simply a scholarly collection of words. In an oral culture, words are cultural artifacts that hold insights into the people, their experiences and their way of life. Studying the language in the manner in which he did gave Hallendy a basis for discussions with the elders as a way of discovering the spiritual or sacred landscape of their existence. Understanding the significance of the vast spectrum of words and expressions related to, for example, sila or the weather, gives us a better sense of the reality of their existence. Being able to read the slightest nuances of the weather and related conditions was critical for survival. Hallendy documented many archaic words and expressions from the elders who have since passed on, underscoring the significance of his work.

This brief description of the Norman E. Hallendy Archives, now housed in its entirety at the McMichael, only begins to touch upon the legacy of this award-winning ethnogeographer. Hallendy’s work has ensured the preservation of a vulnerable segment of the cultural heritage of Canada’s Inuit people. The research value of the Hallendy Archives is potentially more significant because of the conditions under which it was created. It required a special vision to bring together three divergent approaches to achieve a unique perspective that combined the methodical accuracy of an academic with the ability to communicate with the sensitivity of a poet, and the enlightenment to allow one’s journey to be guided by the spirit of the people themselves. It is an honour for the McMichael to be entrusted with both safeguarding and making this national treasure accessible.