Grounds & Trails

Outdoors: Grounds & Art

Art is in our nature. Beyond the galleries, you can explore 100 acres of forested land in the Humber River Valley – from a ridgetop ‘wilderness garden,’ planted by Robert and Signe McMichael to echo the northern forest beloved of the Group of Seven, to the heritage waterway important to indigenous peoples in this area.

Through a network of outdoor paths and hiking trails through natural stands of maple, oak and pine, visitors can explore the Ivan Eyre Sculpture Garden, a series of installations and outdoor sculptures, the Tom Thomson shack, as well as the McMichael Cemetery where six Group of Seven members as well as gallery founders Robert and Signe McMichael have been laid to rest.

Audio Guided Tour

Listen to our audio guided tour. Learn significant facts, insights and details about key landmarks while walking the grounds of the gallery. Enjoy the McMichael in a whole new way!

The Sculpture Garden

The Sculpture Garden meanders across the property at the front of the McMichael. The nine bronze sculptures, donated by artist Ivan Eyre, are part of our permanent collection and can be enjoyed year-round. Eyre is best known for his large landscapes and mythological paintings, and his sculpture is similarly a complex synthesis of Western and non-Western influences.

The Sculpture Garden and its place at the McMichael reinforces the gallery’s mission to showcase the art within our nature and provide visitors with an appreciation of the relationship between the two.

The Garden is open all year long and is beautiful in every season. Watch this video of our Art Conservator performing the annual analysis and restoration of the bronze sculptures.

Minokamik Garden

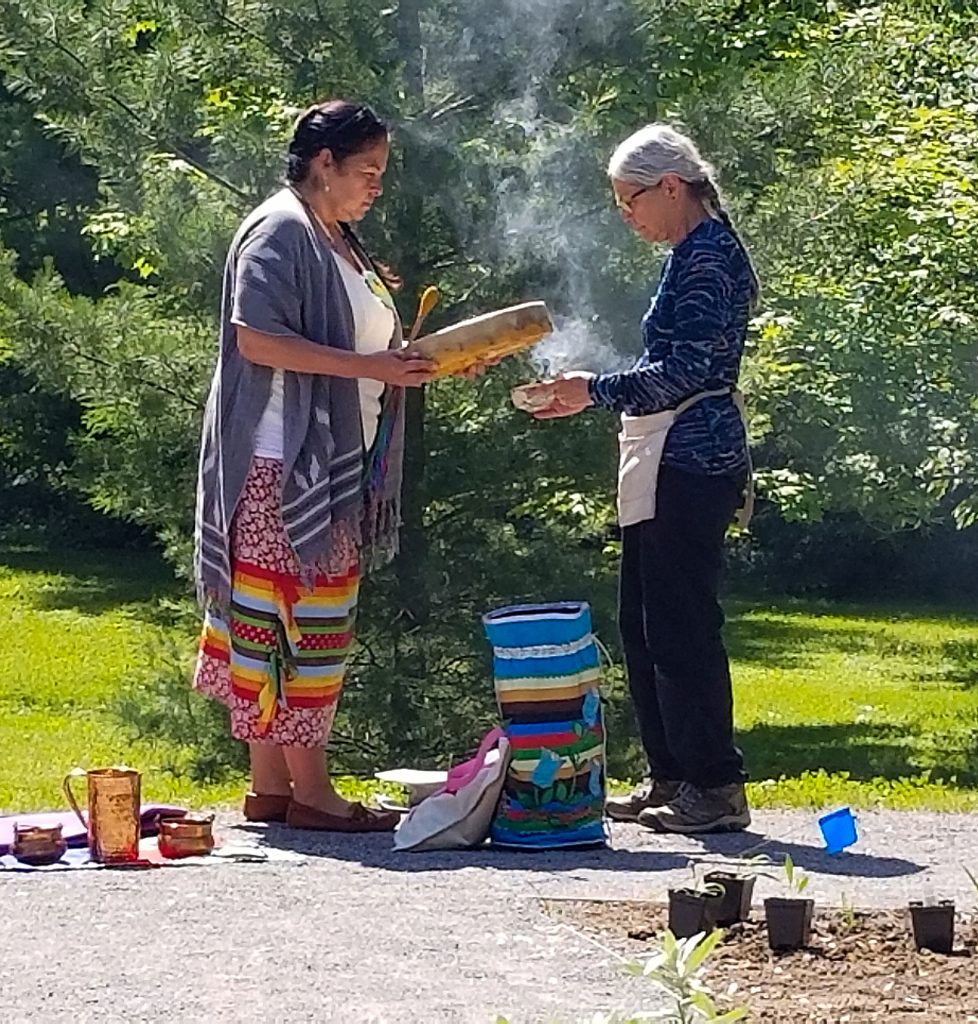

The Minokamik Garden was planted by local community members and school groups from the York Region District School Board in 2019. D

esigned and planted under the guidance of Elder Shelley Charles, Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation, Elder Advisor to the McMichael’s Creative Learning team, and Lynn Short from the Humber College Horticulture Department, the Minokamik Garden represents the commitment of the McMichael’s staff, volunteers, and community members to restoring the land on which the Gallery sits, along the traditional Carrying Place Trail adjacent to the Humber River Valley, to its native flora, promoting biodiversity and providing a space for environmental education.

The design of the garden is based on the traditional Anishinaabe teachings of the Four Directions and includes plantings of sage, pearly everlasting, wild strawberry, sweetgrass, tobacco, and red bee balm among other species.

The name Minokamik, generously provided by Elder Shelley Charles, refers to the good earth, the first scent of the new soils of the spring renewal. It represents the coming together of people from all nations in the restoration of Indigenous plants and creating new interconnected relationships in our mutual stewardship of the earth and our extended family relations.

The leadership and guidance of Elder Shelley Charles and Lynn Short was crucial from the start of this amazing project and the Minokamik garden is just the beginning of our work together in the restoration and stewardship of the land the McMichael is situated on.

“The Minokamik garden is a collective community approach to the restoration of Indigenous plants in the landscape: Truth and Reconciliation at it’s finest! Working with local youth from Kleinburg, Pierre Burton, Woodbridge and Lester B. Pearson Public schools planting and growing Indigenous seeds to transplanting seedlings with Lynn Short from the Indigenous garden at the Humber Arboretum. Minokamik has come full circle. The garden is a celebration of what we all can accomplish together as stewards and earth keepers of Minokamik, the Good Earth. Thank you to the McMichael Volunteers and of the staff for providing the space, time and maintenance for the restoration of Indigenous plants, medicines, and wildlife into the natural environment”. – Elder Shelley Charles

“I am so proud to be part of this wonderful project in collaboration with Elder Shelley Charles and the McMichael Gallery staff. It is so heartwarming to see the way the plants, that we brought from the Humber Teaching Garden, have established in Minokamik. I feel so connected to the garden and all its visitors, especially the pollinators and other creatures that are making their home in the garden. I hope the many human visitors to McMichael will be able to enjoy and learn from this garden long into the future.” – Lynn Short

Tom Thomson Shack

In 1914, Lawren Harris and Dr. James McCallum purchased land on Severn Street in the Rosedale ravine in Toronto on which they built a studio offering low‐rental space for Canadian painters. Now a National Historic Site of Canada, the Studio Building gave artists, including Tom Thomson and A.Y. Jackson, a place to live, work, and socialize.

Behind the Studio Building stood a small shack, previously occupied by a cabinet maker and later used as a tool shed during the studio’s construction. By the fall of 1915, Thomson had moved into the shack apparently out of economic necessity, paying just one dollar a month in rent.

The arrangement allowed the artist to live as he would in the north country – cooking his own meals, sleeping, painting, and hiking through the ravine – while at the same time keeping him in close contact with his fellow painters. The shack was to be Thomson’s home and studio until his untimely death in 1917.

Several changes and repairs were made to the modest building in order to accommodate Thomson, including the addition of a large window along the east wall. The artist also constructed for himself a bunk, shelves, a table and an easel. Thomson’s shack soon became a gathering place for his friends and colleagues. Arthur Lismer, Lawren Harris, J.E.H. MacDonald, F.H. Varley, and Franklin Carmichael among others, were known to assemble there regularly to discuss the news over a pipe and a meal of beans or mulligan stew prepared by Thomson.

After spending the warmer months sketching in the Park, Thomson would return to the Shack to continue his work. During the three winters he spent there, Thomson painted approximately twenty canvases including two of his most celebrated works: The West Wind and The Jack Pine.

After Thomson’s death in 1917, the shack was used occasionally by a number of artists, among them A.Y. Jackson, Fred Varley, sculptor Frances Gage, and a prospector named Keith MacIver, who made a series of repairs to the deteriorating building. It was eventually purchased by Robert and Signe McMichael and moved to the gallery grounds in 1962, along with Thomson’s original easel and two of his palettes. While the details of its full history are somewhat unknown, the Tom Thomson Shack represents an important piece of Canadian history and offers visitors a glimpse into the life and work of one of the country’s most enigmatic artists.

Cemetery

The McMichael cemetery is the final resting place for six members of the Group of Seven, their spouses, and the gallery’s founders, Robert and Signe McMichael. In his book, One Man’s Obsession, Robert McMichael recalls receiving a letter from Jackson in 1967, in which the artist expressed a hope to be buried near Kleinburg. A few months later, while Jackson and Casson were visiting the McMichaels, the idea of a memorial cemetery for members of the Group of Seven began to take shape.

In the spring of 1968, Jackson fell seriously ill and the need for a burial ground on the gallery premises became pressing. The McMichaels had to select an appropriate location for the cemetery that would be accessible, yet quiet and dignified. They soon settled on a small grassy knoll with views of the river valleys, the woods, the Tom Thomson Shack and the distant roofs of the gallery. Later, the McMichaels arranged to have the Department of Highways bring carefully selected slabs of granite, blasted during road building in the artists’ beloved north country, to the site. They were carved by Canadian sculptor E.B. Cox, and used as grave markers.

The Development of the Cemetery

- Arthur Lismer (1885‐1969): Lismer died in Montreal, Quebec on March 23, 1969 and was brought to Kleinburg for burial on April 25, 1969. His wife Esther (1879‐1976) was buried with him.

- Frederick Horsman Varley (1881‐1969): Varley died on September 8, 1969, was cremated on September 13 and interred the following week.

- Lawren Stewart Harris (1885‐1970): Harris died in Vancouver, British Columbia on January 29, 1970 and was cremated. His ashes, along with those of his wife, Bess (1889‐1969), were interred at the McMichael on March 20, 1970.

- Alexander Young Jackson (1882‐1974): Jackson died on April 5, 1974 and was buried in a graveside service on April 8, 1974.

- Frank Johnston (1888‐1949): Johnston died July 9, 1949 and was originally buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto. He was disinterred and reinterred at the McMichael on March 13, 1975. His wife, Florence, is buried with him.

- Alfred Joseph Casson (1898‐1992): Casson died on February 19, 1992 in Toronto and was buried on February 20, 1992. His wife, Margaret (1900‐1992) is buried with him.

- Robert McMichael (1921‐2003): Robert McMichael died on November 18, 2003 and was buried on November 24 following visitation and a funeral service at the gallery.

- Signe McMichael (1921‐2007): Signe McMichael died on July 4, 2007. The gallery was closed for visitation and a funeral held on July 9, 2007.

Sculptures

Pauta Saila (1916 – 2009), Polar Bear, 1967

Limestone, Gift of City of Toronto

Having carved numerous Arctic animal forms, the artist chose to focus on the bear as his primary subject. His approach emphasizes the mass of the form while maintaining sensitivity to detail in describing movement which illustrates the animal’s hunt for food. With his mastery of execution and simplification of forms, Pauta Saila conveys a sense of the presence of the creatures as well as the drama that is being enacted in nature.

David Ruben Piqtoukun (born 1950), INUKSHUK, 1986

Sandstone, On loan from the Province of Ontario

An inukshuk is a cairn made out of pieces of rock, often piled up to resemble a human form. These structures are used by the Inuit to help herd the caribou, and as markers to indicate a particular site. This inukshuk was made to commemorate the first Native Business Summit in June, 1986. In 1987, the inukshuk was donated to the Province of Ontario by the Government of the Northwest Territories and moved to its present location.

Mary Anne Barkhouse (born 1961) and Michael Belmore (born 1971), lichen, 1998

Bronze wolves, transit shelter, Duratrans and metal pole, Purchased with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts Acquisition Assistance Program, and with matching funds from Mr. John F. Bankes and Pamela M. Gibson, Toronto

In this work, the artists address issues of nature versus culture. The role of wolves in this setting is symbolic. They are positioned like silent sentinels. The transit shelter in urban society is associated with protection from the elements as well as serving a commercial purpose. In place of an advertisement, we are presented with the image of Raven. First Nations’ legends often represent Raven as a messenger and liaison between the spirit world and the real world.

Bill Vazan (born 1933), Shibagau Shard, 1989

Granite, On loan from the artist

Constructed from a single piece of Pre-Cambrian Shield granite, Shibagau credits the small creek in eastern Ontario where the stone was found, while Shard makes reference to the science of archaeology. Using modern sandblasting technology, Vazan, who studied the inscribed petroglyphs and pictographs of the First Nations of southern Ontario, has emulated the mark-making of stone-carving tools employed by Canada’s original inhabitants, making reference to ancient methods of documenting human interaction with the land.

The sculpture in the background of this photograph is called “Peace Making Machine” and was made out of ash wood planks and steel pipe by Ryszard Litwiniuk in 2011. The sculpture was part of the McMichael Artists-In-Residence Program and The Tree Project, created in celebration of the McMichael legacy and our deep-rooted connection to art and nature. The Tree Project reaffirms our affiliation with our community and the land through the symbolic wholeness of the tree — an emblem that embodies the essence of the McMichael gallery and grounds as a revered cultural landscape.